Should Corresponding Authors Use Their Personal Email?

My unasked opinion

TL;DR

📧 Institutional emails = credibility in academia.

But they vanish the moment we leave the lab — taking future collaborations with them.

So what’s the smarter move?

Use your institutional email for submission.

Add a professional personal email as backup.

Keep ORCID updated for long-term contact.

That’s the quick version. But the real story (and what most don’t talk about) is much more interesting…😉

Since I started ✍️ press releases about scientific papers, I’ve been reading far more manuscripts than ever. And one small but telling pattern keeps popping up. Two types of corresponding authors:

The ones using their institutional email.

The ones using their personal email — often Gmail.

At first glance, it feels trivial. But in academia, the email we choose says more than we might think.

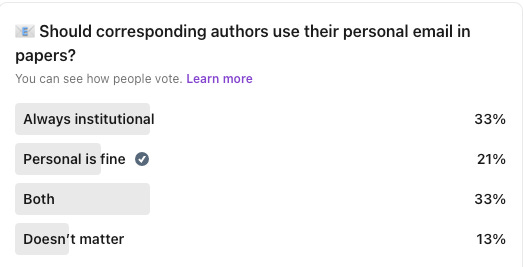

What’s interesting is that my opinion as a 👩🔬 researcher isn’t the same as my opinion as a 🧐 reviewer. So, to test my assumptions, I asked my LinkedIn community what they thought — and did some research of my own. Here’s what I found…

The "Unwritten Rule"

There's no universal policy forcing us scientists to use our institutional email when submitting a paper. Still, professional convention expects it.

Most journals, conferences —me as a reviewer— prefer institutional emails because they:

✅ Confirm credibility — they show that the author is tied to a recognized institution.

🔍 Simplify verification — editors and reviewers can quickly check affiliation.

And here’s my confession: when I see something like 652490@gmail.com as the contact email, I hesitate.🤔 It immediately raises questions and, during peer review, slows me down because I feel the need to double-check that it’s a real researcher and not… something else.The system relies on trust and recognition. But in practice, it’s not as reliable as we like to think.

The Problem No One Talks About

As a researcher, every time I've changed institutions, I've been lucky if my email account stayed active for more than a month. So, if I had been a corresponding author on a freshly published paper, any follow-up emails would have disappeared into the void 🕳️.

And I know I’m not the only one. I've often emailed corresponding authors, only to find they no longer work at the institution and can’t be reached. This is especially common in today’s academic job market, where researchers frequently move between postdocs, temporary positions, and institutions.

From a practical standpoint, and from a researcher point of view, institutional-only contact information is fragile. This creates a real barrier to scientific communication and collaboration, potentially limiting the impact and follow-up discussions around published research.

At the same time, I have to admit: I don’t want everyone to have my personal email either 🚫📩. That crosses into privacy — and in some cases, even data protection concerns.When Personal Emails Make Sense

There are situations where a personal email is the logical choice:

Independent researchers without institutional affiliation.

Scientists between jobs or fellowships.

Researchers at institutions without reliable email systems.

If this applies to you:

✉️ Use a professional-looking address (avoid nicknames or dates).

🏫 Clearly list your institutional affiliation in the paper.

📑 Explain your situation in the cover letter if needed.

📞 Consider reaching out to the journal editor beforehand to discuss their preferences.

My Unasked Opinion

If you're affiliated with an institution, yes — use your institutional email for the submission. It avoids unnecessary red flags 🚩 during peer review and keeps everything "by the book." But also consider adding a professional personal email as a backup at the end of the manuscript, for example.

This way:

You maintain credibility during submission.

You remain reachable long after you've moved on.

Readers, journalists, and potential collaborators can still contact you years later.

Important considerations:

🏫 Check your institution's policies first — some organizations have guidelines about mixing professional and personal contact information.

🔒 Be mindful of data protection regulations that might affect how you handle research-related communications through personal accounts.

🧪 Consider whether your research involves sensitive topics where maintaining strict institutional boundaries is crucial.

Modern Solutions Worth Considering

Beyond the dual-email approach, researchers increasingly rely on persistent identifiers like ORCID profiles 🔗, which can maintain updated contact information across career moves. Many journals now encourage or require ORCID IDs, making them an excellent complement to traditional institutional email addresses. 👍🏻

Professional networking platforms like ResearchGate or LinkedIn 💼 can also serve as good backup contact methods, though they shouldn't replace direct email contact in your manuscript.

Final Thoughts

Tradition says: institutional email first.

Reality says: don't let your future collaborations die with your old email account.

The goal is to balance ⚖️ professional expectations with practical accessibility. Whether that means using both email types or leveraging on persistent identifiers like ORCID, the 🔑 is thinking beyond publication day.

Your research deserves to be discoverable and your expertise accessible — not just until the paper is published, but for years afterward when the real scientific conversations begin.💬

💡 What about you?

Thanks for reading it! ❤️

Cátia